IN THE SUPREME COURT OF SWAZILAND

JUDGMENT

HELD AT MBABANE CIVIL APPEAL CASE NO: 21/2017

In the matter between:

E 1 RANCH (PTY) Ltd APPELLANT

And

EARLY HARVEST FARMING (PTY) Ltd RESPONDENT

Neutral Citation: E 1 Ranch (Pty) Ltd v Early Harvest Farming (Pty) Ltd

(21/2017) [2017] SZSC 68 (1 December 2017)

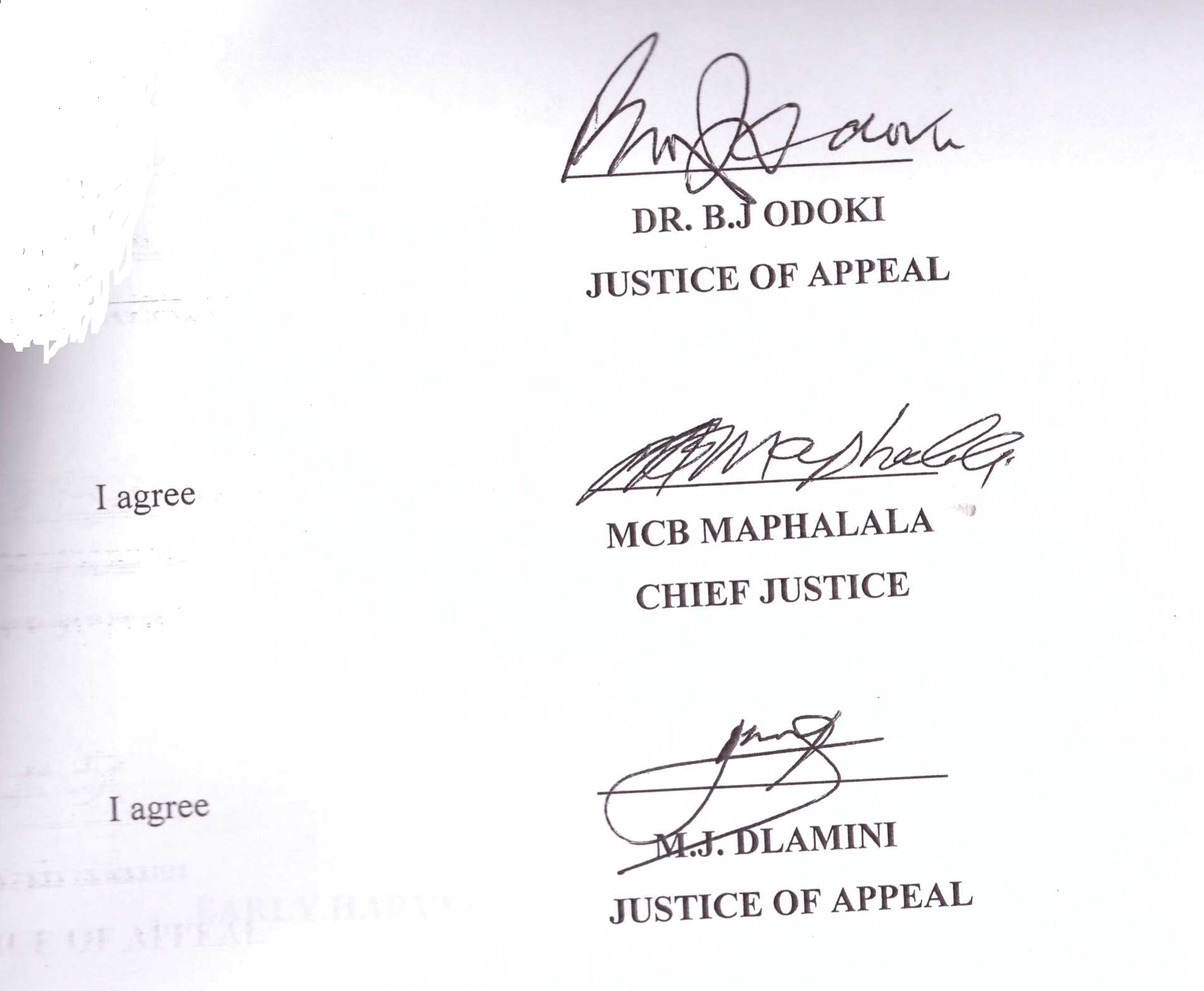

Coram: MCB MAPHALALA CJ

DR. B. J. ODOKI JA

M. J. DLAMINI JA

Date Heard: 20 September 2017

Date delivered: 30 November 2017

Summary: Landlord and Tenant ‒ Order confirming perfection of landlords hypothec ‒ Whether parties agreed to a verbal month to month lease ‒ Whether lease still subject to negotiations ‒ Invoices for rentals submitted to Appellant monthly ‒ Appellant claiming VAT on bases of monthly invoices ‒ Negotiation for lease continuing to be held ‒ Whether matter amicably settled ‒ Whether dispute of fact existed between the parties ‒ Whether Appellant did not disclose all the facts ‒ Held, Court a quo was correct in holding that there was a month to month lease, that no settlement was concluded and no real material disputes of fact existed requiring matter to be sent for oral evidence ‒ Appeal dismissed with costs.

JUDGMENT

![]()

DR. B.J. ODOKI J.A

[1] The Respondent brought an application in the Court a quo seeking an order to perfect the landlord’s hypothec and related orders. The orders sought included an order that pending payment of the arrear rental in the amount of E4, 194,337.75 claimed by the Respondent from the Appellant in respect of the remaining extent of Farm No 8 situate in the District of Manzini and Farm Nooitgedacht No 99, situate in the Manzini District, the Appellant be interdicted from removing or disposing of any of the movable assets which shall include but not limited to the agricultural crops and livestock from the premises.

[2] The Respondent also sought for an order, that on confirmation of the Rule Nisi the Respondent be allowed to sell all the movable assets either through public auction or private treaty. The Respondent further sought an order for cancellation of the lease, and an order for ejectment of the Appellant from the E 1 Ranch Immovable Property and Horse shoe Immovable Property. The Respondent finally sought for an order directing the Deputy Sheriff to forthwith serve the order upon the Appellant, attach and secure all movable assets, agricultural crops and livestock upon the premises, make an inventory thereof and make a return to the Respondent and the Registrar of what he has done in execution of this order.

THE BACKGROUND

[3] The background to this appeal is as follows. The Respondent claimed that sometime in October 2013 and February 2014, there was concluded between itself and the Appellant two respective verbal lease agreements (being month to month leases) in terms of which it leased to the Appellant its properties namely the E 1 Ranch Farm and the Horse Shoe Farm, which it had just purchased.

[4] The rental was allegedly to be calculated following a certain formula in each case which was however certain. It was to be the total purchase price of the property concerned multiplied by 8% which was to be divided by the number of days in a year in order to get the daily rate.

This product would itself be multiplied by the number of days in a given month so as to come up with a monthly rate or monthly rental. There would also be added to that figure 14% as value added tax. This formula applied to both farms.

[5] It was also allegedly a term of the lease agreement as well that the rental for each month would further incorporate what was called a social responsibility component calculated through finding 0.50% of the purchase price of the farm divided by 365 days a year so as to come up with a daily component which would in itself be multiplied by the number of days each particular month so as to come up with a month’s social responsibility component.

[6] As a result of the application of these formula, in order to determine both the rental qua plus the VAT and the Social Responsibility component, the average monthly rental was a sum of about E175, 410.30 for the E 1 Ranch, whilst it was to be E57, 769.55 for the Horse Shoe Farm.

[7] The Respondent used to issue monthly statements on the rentals due for each month. The Appellant did not dispute its liability to pay the rentals as set out in the monthly statements.

The Appellant used to claim the VAT input from its customers which it required to pay in terms of the amounts for rentals as revealed in the same statement.

[8] At one point the Appellant requested the Respondent to consolidate all the invoices it had issued into one statement which was done. The Appellant further asked the Respondent that there should be a moratorium on the rentals.

[9] Without disputing the rentals, the Appellant did not pay the rentals claimed, but kept on receiving the rental statements or invoices sent to it. The Appellant, however, claimed VAT input on the said statements. The non-payment of rentals occurred for a period of about two years.

[10] While the statements for rentals kept being issued to the Appellant without disputing them, the parties were busy engaged in negotiating a fixed term lease. This kept being negotiated without agreement being reached. Later the Respondent took a decision to have the Appellant vacate the farms so that it could establish a dairy project on them.

[11] After the Court a quo had granted ex parte application with a rule nisi being issued calling upon the Appellant to show cause why it could not be ordered to pay the arrea rentals together with interest thereon, as well as ejectment of the Appellant from the Farms, the Appellant opposed the order when served with it.

[12] The Appellant raised several points of law which included the following:

The application was allegedly not urgent or such urgency as could be established was of the applicant’s own making.

The application has a foreseeable dispute of fact on the existence or otherwise of a verbal lease agreement which necessitated that the application be dismissed.

Notwithstanding that the application had allegedly approached the matter on an ex parte basis, it failed to make a full and proper disclosure of all the material facts in the matter which were within its knowledge.

[13] The Appellant denied the existence of a verbal lease agreement between the parties. The Appellant contended that a lease agreement was still being negotiated between the parties which it said was one of the facts the Respondent had failed to disclose it its application. It was revealed that numerous draft lease agreements had been sent to the Appellant for signature, which it did not sign as it was raising new issues for inclusion in the said agreements.

[14] The Appellant claimed that several letters which had been exchanged between the parties culminated in an agreement.

However, the Respondent contended that the Appellant failed to unequivocally accept the final offer given to it within the period stipulated, and therefore there was no settlement of the matter

[15] The learned judge in the Court a quo allowed the application and made the following orders;

“1. The Respondent be and is hereby ordered to pay applicant the sum of E2, 936,450.62.

2. The Respondent is to pay interest on the amount stated in order 1 above at 9% a tempore moral from the date of the institution of the proceedings to that of payment.

3. The Respondent is ordered to pay the costs of the main application which shall include the costs of counsel reckoned in terms of Rule 68.

4. On the application to revive the rule that had lapsed, each party to bear its costs.”

THE GROUNDS OF APPEAL

[16] Being dissatisfied with the above decision and orders the Appellant appealed to this Court on the following grounds;

The Court a quo erred by failing to refer the matter to trial or to direct that oral evidence be heard on the material disputes of fact which could not be resolved in the application proceedings.

The Court a quo erred in finding in paragraph [35] of the judgment that a verbal month to month lease agreement had been concluded.

It further erred in finding in paragraph [6] of the judgment that the respondent had alleged that two verbal month to month leases were conclude in October 2013 and February 2014.

The Court a quo erred in its findings in paragraph [35] in that the respondent had alleged in its founding affidavit that the period of the verbal lease was one year which could be extended for a further period.

The respondent had also alleged in its founding affidavit that the alleged verbal lease of 1 October 2013 included Horseshoe Farm. The Court a quo failed to have regard to evidence that Horseshoe Farm was only acquired in February 2014 and as such could not have formed part of discussions in October 2013. The Court a quo also erred in its reference in paragraph [6] of the judgment to two verbal lease agreements in that there was no allegation in the founding affidavit of a separate lease agreement in February 2014.

The Court a quo erred in finding that a Practice Directive of the Chief Justice which refers to a practice for the perfection of a landlord’s hypothec and for the payment of arrear rentals stipulated that arrear rentals could be claimed in terms of a rule nisi operating without interim effect. The Court a quo erred in that the form of prayer suggested in the directive required that a claim for area rentals be heard and adjudicated upon at such time and in accordance with such procedures as the Court may deem fit. In the case of a Court a quo material dispute of fact as in this case the Court a quo ought to have ordered the matter to trial.

The appellant also alleged counterclaims in its answering affidavit and sought that such claims also be refereed to oral evidence.

The Court a quo erred in finding in paragraph [43] that the counterclaims could be instituted as independent claims and that the appellant would not be prejudiced by the respondent’s claim proceeding without the counterclaim being adjudicated upon. The Court a quo erred in that the matter including the counterclaims ought to have been referred to trial or oral evidence.

The Court a quo erred not finding that the respondent had failed to make full disclosure of all the material facts that might have affected the granting of an order ex parte. It ought to have found that the protracted negotiations which called into question the existence of the lease law ought to have been disclosed and it ought to have exercised its discretion to dismiss the application.

The Court a quo erred in finding that there had not been a settlement of the dispute.

ARGUMENTS OF THE APPELLANT

[17] The Appellant submitted that there were material disputes of fact which could not be resolved in application proceedings on the question whether a verbal month to month agreement had been concluded. It was the contention of the Appellant that there were material disputes of fact in respect of the negotiations relating to the nature of the lease agreement in which the parties were unable to reach agreement.

[18] The Appellant argued that the material disputes of fact were that;

The alleged verbal lease agreement had been entered into telephonically on 1 October 2013, whereas the Appellant claimed that the terms of the lease were being negotiated through sending various draft agreements and that the Appellant proposed long lease.

The Appellant disputed that the receipt of invoices which indicated that an agreement had been reached in that a commencement date and payment intervals as part of a long lease were being negotiated.

The Appellant alleged that negotiations commenced with a first draft which was sent to it in October 2013. This draft provided for a one year lease which the Appellant contends was untenable in an agricultural context. It is accordingly disputed that an oral one year lease had been concluded.

The Court a quo erred in finding in the judgment that the various draft lease agreements sent in October 2013 November 2013, March 2013, April 2014 and June 2014 amounted to the discussion of a further agreement on further terms after the conclusion of an oral agreement.

The various drafts and revised proposals in the drafts from October 2013 to June 2014 raise material disputes of fact which contradict the allegation in the founding affidavit that a verbal lease agreement for an initial period of one year had been concluded.

[19] The Appellant maintained that in the ex parte urgent application the Respondent alleged that a verbal lease agreement was entered into telephonically through discussion on 1 October 2013, and that the Respondent choose to depict the telephone discussion as resulting into a binding lease whereas it failed to disclose to the court that extensive negotiations followed and numerous drafts of proposed agreements were produced. The Appellant submitted that on the evidence before the Court there is no basis to conclude that a binding lease was concluded in October 2013.

It was contended that the draft agreements referred to in the answering affidavit contained clauses in respect of duration and other terms upon which the parties could not reach agreement. It was argued that these were material facts in respect of an alleged lease which the Respondent failed to disclose to the Court a quo in the ex parte urgent application.

[20] The Appellant submitted further that the allegations made by the Respondent in its Founding Affidavit that it was agreed that the Appellant would pay a deposit equivalent to two months rent and that it would be for one year does not accord with a finding that there was a month to month lease.

[21] On the issue whether the Respondent failed to disclose material facts, the Appellant submitted that the Respondent failed to reveal the various proposals and negotiations which the parties were engaged in, and that failure to do so was an abuse of the procedures of the Court a quo. The Appellant disputed the Respondent’s answer that it was not obliged to disclose these matters because they were not material. It was the contention of the Appellant that the Respondent was required to make full disclosure of all material facts that might affect the granting to the order ex parte.

[22] The Appellant also argued that given the nature of the farming operations the Appellant was engaged in and the business relationship between the parties, it is inconceivable that the form of lease required or concluded could be a month to month to sustain the farming operations.

[23] It was the contention of the Appellant that it had proposed that the duration of the lease should be for a period of ten years with an option to purchase the farms at the end of the period, but the Respondent conceded that it did not agree that the lease should be for a period of ten years. According to the Appellant, this amounted to an admission that there was such a proposal. The Respondent argued that this concession by the Respondent was inconsistent with the finding of the Court a quo that a month to month lease was concluded.

[24] The Appellant pointed out that it sought a two year moratorium for the purpose of re-establishing the sugar cane and vegetable business and to establish the cattle business. The Appellant conceded that many proposals were discussed as the terms of agricultural leases differ from usual commercial leases.

[25] With regard to the VAT claims, the Appellant submitted that merely because claims were made on invoices is not proof that a lease on the terms alleged by the Respondent had been concluded.

[26] It was the contention of the Appellant that the failure to prove a lease agreement in the Founding Affidavit, the failure to disclose material facts in the Court a quo, and the material dispute in respect of the negotiations relating to the conclusion of a lease agreement, required a referral of the matter to trial or direction that oral evidence be led.

[27] The Appellant submitted that it claimed a counter-claim in the total amount of E7, 060,328.00 which the Respondent admitted in part in respect of invoices for work done although in a slightly different amount of E1,257,887.13.

[28] In reply to the contention by the Respondent that the counter-claim is not relevant to the current issue being the hypothec, the Appellant submitted that the counter-claim is indeed relevant in an application where the Respondent sought confirmation of the rule and or confirmation of an order allowing it to sell all movable assets in a public auction. Moreover, the Appellant argued, the amount sought by the Respondent in payment was not based on a proved lease and in any event it is significantly less than the counter-claim.

[29] The Appellant argued that the Court a quo erred in holding that the counter-claims could be instituted as independent claims and that the Appellant would not be prejudiced by the Respondent’s claim proceedings without the counter-claim being adjudicated upon. It was the contention of the Appellant that both the Respondent’s claim and the Appellant’s counter-claim ought to have been referred to oral evidence.

[30] The Appellant submitted that the counter-claim is clearly a defence to the Respondent’s claim on which there would be no liability in the event that a counter-claim succeeds and, therefore, there is very substantial prejudice in failing to adjudicate on the counter-claim as part of the application proceedings.

[31] With regard to the issue whether there was a settlement, the Appellant submitted that the Court a quo erred in finding that there had not been a settlement of the dispute on a assessment of the totality of the correspondence. It was the contention of the Appellant that in as far as the letters dated 18 May 2015, 20 May 2015 and 29 May 2015 were the subject of disputed interpretations, the Court a quo erred in declining to hear oral evidence from the attorneys involved as specifically sought.

[32] In conclusion, the Appellant submitted that application ought to have been dismissed or alternatively the disputes regarding the alleged lease and claim of rent as well as the counter-claim ought to have been referred to oral evidence and or trial, as they could not be resolved on the papers.

ARGUMENTS BY THE RESPONDENT

[33] The Respondent submitted that the facts in this case demonstrated unequivocally that no true dispute of fact has been raised and that the allegations or denials of the Appellant are so far-fetched or clearly untenable that the Court a quo was justified in rejecting them merely on the papers.

[34] It was the contention of the Respondent that the repeated references to a moratorium, the affirmative statement that input VAT had necessarily to be claimed upon receipt of the invoices provided, and the failure to record any dispute as to the indebtedness evidenced in the invoices, provides unequivocal proof of the indebtedness. The Appellant also argued that the moratorium sought by the Appellant was not granted and therefore its indebtedness is due and payable.

[35] The Respondent asserted that on 1 October 2013, it let the farm E 1 Ranch to the Appellant in terms of an oral lease together with another property it acquired namely Horse Shoe Farm. According to the Respondent, the rental for E 1 Ranch was calculated so as to provide an 8% return on the purchase price that the Respondent paid (E25, 107, 750.00) which equated to a daily amount of E5 503.07. VAT at 14% was to be added to this amount. Multiplying this amount by the number of days in any given month, provided the monthly rental exclusive of VAT. The Appellant was also obliged to pay a social responsibility levy in an amount of E323.94 per day.

[36] The rental for Horse Shoe Farm was calculated on a similar basis on a purchase price of E8,005,973.00 and equated to a daily rental amount of E 1 755.00. The corporate social responsibility levy for Horse Shoe Farm was E109.67 per day.

[37] The Respondent submitted that the Appellant took occupation of E 1 Ranch on 2 October 2013 and of Horse Shoe Farm on 7 February 2014. The Appellant was charged rental for E1 Ranch as from October 2013, but the social responsibility levy was waived up to the end up and including December 2013. Rentals and levies for the Horse Shoe Farm became payable as from February 2014. The Respondent annexed a full reconciliation of amounts owing and demonstrated that an aggregate amount of E4,194,337.75 in rentals and levies was owed as at 1 February 2015.

[38] The Respondent maintained that no disputes as to the indebtedness have been raised. On the contrary, input VAT has been claimed by the Appellant for a period from October 2013 to September 2014, not withstanding that rentals were not paid. Whilst monthly invoices were raised, the Appellant asked the Respondent to consolidate all invoiced amounts for the period October 2013 to March 2014 into a single invoice. This was done and an invoice dated 1 March 2014 was issued to the Appellant.

[39] It was the contention of the Appellant that in the contemplation of the conclusion of a written lease agreement, the oral agreement was initially for a period of one year commencing from October 2013 which could be extended and that after it expired on 1 October 2014 the Appellant remained in occupation of the two properties on a month to month basis.

[40] On the issue of the indebtedness, the Respondent submitted that it is common cause that the Appellant took possession of the two farms, that the Respondent has invoiced the Appellant in the aggregate sum of E4,194,337.75, and that the Appellant has not paid any part of this sum. It was the contention of the Respondent that the Appellant admitted receiving the invoices but did not dispute the amounts reflected in the invoices nor did it claim that the rentals were not payable, nor did it suggest the amount of rentals payable. Instead of disputing the rentals claimed, the Appellant requested for a moratorium postponing payment of the rentals. The request for a moratorium is consistent only with an admission of indebtedness.

[41] The Respondent argued further that the Appellant merely denied its indebtedness in its answering affidavit and claimed that in any event it has a counter-claim. It was the submission of the Respondent that an honest litigant would assess the indebtedness which it believes is owed and would have tendered this amount.

[42] Regarding the claim by the Appellant that by claiming VAT input, it was “not acknowledging that invoices were accepted and /or that they were due and payable, but was only complying with the legal requirement that entails VAT being payable and/or claimable on presentation of the invoice,” the Respondent submitted that the Appellant was either acknowledging liability to the Respondent or it committed a fraud on the revenue authorities by making the VAT input claim in circumstances where it was not entitled to claim the amounts it did.

[43] It was the contention of the Respondent that in making the claims for VAT the Appellant necessarily acknowledged that the amounts claimed by way of the input arose out of the issue of invoices for amounts owing by it to the Respondent. The Respondent argued further that in making those claim, the Appellant necessarily represented to the Revenue Authorities that the amounts, reflected in the Respondent’s invoices were owing and that it was liable to make payment of those amounts. Therefore, the Respondent submitted, the Appellant could not have claimed input VAT if it disputed the invoices, the Appellant made reference to sections 14,18 (i),25,28 (i), 28 (4) 31,and 32 of the VAT regarding when VAT is payable.

[44] The Respondent maintained that if the Appellant disputed its indebtedness to the Respondent, it would have placed such a dispute on record. However, on the contrary, there is no single document annexed to the papers in which such dispute is raised. The Respondent also argued that the Appellant is deemed to have acquiesced in the debt by its conduct. Reference was made to the case of Mc Williams v First Consolidated Holdings (Pty) Ltd 1982 (2) SA 1 (A) where it was held that where repudation of an assertion is expected in commercial practice, a party’s silence and inaction may be taken to constitute admission by him of the truth of the assertion.

[45] The Respondent submitted that in the circumstances of this case, payment was due forthwith upon the rendering of invoices or at best for the Appellant to pay within a reasonable time.

The Respondent cited the case of Mckay v Naylor 1917 PTD 533 at pages 538 to 539 where it was held that “ The general rule of law is that obligations for the performance of which no definite time is specified are enforceable forthwith but the rule is subject to the qualification that performance cannot be demanded unreasonably so as to defeat the objects of the contract or to allow an insufficient time for compliance.”

[46] Regarding the issue whether there was a dispute of fact in this case requiring the matter to be referred to trial, the Respondent submitted that no true dispute of fact has been raised and that the allegations or demands of the Appellant so far-fetched or clearly untenable that the Court is justified in rejecting them merely on the papers. In support of its submission; the Respondent referred to case of Plascon-Evans Paints (Pty)Ltd v. Van Riebeek Paints (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 623.

[47] The Respondent submitted that the repeated references to a moratorium, the affirmative statement that input VAT had necessarily to be claimed upon receipt of the invoices provided and the failure to record any dispute as to the indebtedness evidenced in the invoices provides unequivocal proof of the indebtedness.

[48] On the issue whether the matter had been settled the Respondent argued that the assertion by the Appellant had been raised only in the affidavit filed in answer to the application for the reinstatement of the provisional order of attachment. Making reference to the various correspondences that were exchanged between the parties especially Annexes “ SSA 5,” the Respondent submitted that their analysis leads to the conclusion that it is apparent from the Appellant’s own documents that the matter was not settled. The Respondent maintained that the matter was not settled because by the time the letter “SSA 5 (a)” was written making a counter offer to the Respondent’s offer of 15 May 2015, the offer had expired on 18 May 2015. Therefore, there was no acceptance of the offer within the stipulated time frames.

[49] As regards the counter-claims, the Respondent submitted that where a counter-claim is raised in motion proceedings, whilst this may be adjudicated upon pari passu with the claim in convention, the Court retains an overriding discretion to refuse to stay judgment on the claim in convention particularly in circumstances where the Court is somewhat skeptical about the merits of the counter-claim. In support of this submission, the Respondent cited the cases of Amavuba (Pty) Ltd v. Pio Nobilis Landgoed (Edms) Bpk 1984 (3) SA 760 (N) and Truter v. Degenaar 1990 (1) SA 206 (T) at 211 – E – F. Reference was also made to Herbstein Van Winsen”s Civil Practice in the High Courts of South Africa Page 670.

[50] The Respondent maintained that this Court should not interfere with the discretion that the Court a quo exercised in granting judgment and not postponing the matter for determination of counter-claims of which “scant detail” has been given. It was the submission of the Respondent that once indebtedness has been established the appeal should be discussed with costs including certified costs of Counsel.

CONSIDERATION OF THE ISSUES AND ARGUMENTS

[51] The main issues raised in the grounds of appeal and arguments of both parties are as follows:

1. Whether the parties concluded a verbal month to month lease agreement.

2. Whether the Respondent failed to disclose material facts.

3. Whether there were facts material disputes of fact which could not be resolved on papers.

4. Whether there had been a settlement of the dispute.

5. Whether the counter claims ought to have been adjudicated upon together with the claim.

[52] The above issues are more or less the same as those identified by the Court a quo at the hearing of the matter and findings made on them. The learned judge in the Court a quo did observe that it was common cause that the Appellant was given and did receive the two properties for its temporary enjoyment.

The learned judge also noted that while the Respondent stated that the rentals were calculated in terms of an agreed formula in order to come up with the monthly rentals, the Appellant denied this and argued that the rent was exorbitant.

[53] In dealing with the question whether in these circumstances it could be said that there was concluded a lease agreement, the learned Judge stated;

“[30] It cannot be denied from the facts that the applicant religiously sent the Respondent monthly statements depicting the amount of rentals as calculated in terms of the formula referred to above for each one of the properties alleged to have been under the leases. This exceeded a period of over two years. Instead of disputing the rentals allegedly owed by it and clarifying the position under which it came to occupy the premises, the Respondent at one point asked the applicant to consolidate the invoices into one and charged its customers VAT claimed from it by the Applicant in terms of the statements sent to it monthly. At one stage it asked for a moratorium on the rentals, which was not consistent with the conduct of one who knew nothing or who did not owe the rentals claimed.

[31] The point being made is simply that if the Respondent disputed its indebtedness, it would have refuted or disputed the statements claiming rent from it and it would not have asked for their consolidation.

It similarly would not have claimed the VAT input on the basis of the amounts reflected on the same statements. By claiming payment of the VAT input based on the same amounts as reflected on the statements and also asking that the statements be consolidated into one statement there can be little doubt that the Respondent was actually acknowledging its indebtedness. Having acknowledged it indebtedness in the aforesaid manner, the Respondent was thus approbating and reprobating or blowing hot and cold at the same time, which is a practice that the law does not countenance. See in this regard Sandown Travel (PTY) LTD VS, Cricket South Africa [2012] ZAGPJHC 249 or 2013 (2) SA 502 (G5J).

[32] On the Respondent’s having asked for a moratorium on the rentals for two years, the law is very clear that implicit on a moratorium is an acknowledgment of indebtedness and requesting that the payment of the said debt be postponed for the specified period which in this matter was two years.

[54] The learned judge concluded that considering the evidence on the whole, the only conclusion to draw was that a verbal month to month lease agreement had been concluded between the parties.

This is how the learned judge put it:

[35] These facts, taken cumulatively, point to one conclusion and one conclusion only that a verbal month to month lease agreement had been concluded between the parties and that the Respondent was failing to settle same. This is because the conclusion I have reached is consistent with all the facts and is the only reasonable one to draw from the facts which is what the principles of the law of evidence confirm can be used to reason by inference. See in this regard Hoffman and Zeffert’s South African Law of Evidence 4th Edition, Butterworths at page 589 – 590. See also R V Blom 1939 AD 202 at 203,”

[55] I am unable to fault the conclusion reached by the learned judge in the Court a quo that on the basis of all the evidence adduced by the parties the only reasonable conclusion to be drawn is that the parties concluded a verbal lease agreement. There is no doubt that the Appellant was in occupation of the farms for about two years. It is also common ground that the Respondent religiously sent monthly invoices for the rentals calculated according to the formular agreed. The Appellant did not dispute the monthly amount claimed, but instead used the invoices to claim input VAT, thereby acknowledging that it was liable to pay the monthly rentals. The Appellant even requested for consolidation of the invoices into one document and also requested for a moratorium postponing to pay rental for two years which was not granted. However, the Appellant did not pay any part of the rental claimed.

[56] The Appellant has argued that there was no lease agreement since the parties were still negotiating for a long lease of two or ten years. It is common ground that these negotiations were protracted and were not concluded with the lease agreement the Appellant desired. It is also true that the initial proposal was that the Appellant should have a lease for one year. However none of these proposals resulted into an agreement and the Appellant remained occupying the farms on a month to month basis. That is why the rentals were being calculated and submitted on a monthly basis.

[57] The next issue is whether there were material disputes of fact which could not be resolved on the papers. The Appellant argued that among the material facts not disclosed by the Respondent were that the parties were still negotiating an agreement and therefore in reality there was no lease agreement concluded.

[58] In dealing with this issue, the learned trial judge in the Court a quo stated:

“[37]Having already found that there was in existence a month to month lease agreement, it is clear that there could be no merit in the contention that there was no disclosure of the fact that a lease agreement was still being negotiated between the parties. I am of the view that from the facts of the matter, all the Applicant needed to disclose in order to obtain the relief it sought was disclosed.

In order to obtain an order perfecting the Landlord’s hypothec the Applicant had to disclose in my view that there had been concluded a month to month lease agreement between the parties and that the Respondent was in arrears with the payment of rentals including his awareness of such arrears. All these factors were in my view disclosed.”

[38] It also has to be clarified that it is in law not an unknown phenomenon that parties can conclude a fully binding contract while agreeing to discuss a further one or its further terms. This principle is expressed in the following words in Kerr’s The Principle of the Law of Contract, 6th Edition at page 37;

“There is of course, no reason why parties should not enter into a fully binding contract while expressly or impliedly agreeing to discuss the addition of further terms, perhaps very important ones, after the commencement of the contract. If the further terms are not agreed, the original contract stands.”

[59] I agree with the learned judge that the failure to disclose that negotiations were still going on at the time the application was lodged was not a material fact in view of the finding on the first issue that the parties had concluded a verbal month to month lease. The negotiations for a long lease were ongoing but yielded no agreement. The negotiation could not postpone payment of monthly rentals when the Appellant was in occupation of the property.

Even by operation of law, the parties are deemed to have concluded a periodic lease whose rent was determined by the intervals at which it was demanded and became payable. It was immaterial that the parties were negotiating for a longer lease. The position would only have changed if the long lease desired by the Appellant had been concluded.

[60] The next issue is whether there were disputes of fact which could not be resolved on the papers. The alleged disputes of fact were whether the lease agreement was still being negotiated, and the contention that the Appellant had several counter claims against the Respondent. In dealing with this issue, the learned judge stated;

“[45] It should be highlighted that it is not every dispute of fact that would prevent the determination of a matter on the papers or that would render application proceedings inappropriate. A dispute would result in that if it is a genuine or real one and on whether it is a material or relevant one. This position was put succinctly by the Supreme Court in Nokuthula N. Dlamini Vs Goodwil Tsela Supreme Court Civil Appeal Case No. 11/2012 in the following words at paragraph 29 of the Judgment;

“….It will amount to an improper exercise of discretion and an abdication of Judicial responsibility for a court to rely on any kind of dispute of fact to conclude that an application cannot properly be decided on the affidavits.

The Court has a duty to carefully scrutinize the nature of the dispute with a microscope lense to find out-

(i) If the fact being disputed is relevant or material to the issue for determination in the sense that it is so connected to it in a way, that the determination of such an issue is dependent on or influenced by it;

(ii) If the fact being disputed, though material to the issue to be determined, but the dispute is such that by its nature it can be easily resolved or reconciled within the terms of the affidavits.

(iii) If the dispute of a material fact is of such a nature that even if not resolved, it does not prevent a determination of the application on the affidavits.

(iv) If the dispute as to a material fact is a genuine or a real dispute.

[61] The learned judge also referred to paragraph [30] of the Nokuthula N. Dlamini vs Goodwill Tsela judgment (Supra), where the Supreme Court elucidated the position even further as follows;-

“[30] If the dispute on a material fact is not genuine or real, then the application can be decided on the affidavit.

This can arise where the denial of fact is vague, evasive or barren or made in bad faith to abuse the process of court and vex or oppress the other party. A frivolous denial raised for the purpose of preventing a determination of the application of the affidavits or to investigate a dismissal of the application or cause a trial by oral evidence or other evidence thereby delaying and protracting the trial as a stratagem to discourage or frustrate the applicant is a gross abuse of process. We cannot close our eyes to the high incidence of abuse of court process. Parties often times, do not show a readiness to admit liability even when it is obvious that they have not defence to an application or a claim. Such a party whether or not he or she is a Defendant or Respondent, tries to foist on the Plaintiff or Applicant and the court a wasteful trial process for a dismissal of the application through frivolous denials. The object of Rule 6 is to avoid a full trial when there is no basis for it and avoid delay and protracted trial in such cases. It is the duty of a court to ensure that a law meant to facilitate quick access to justice through the expeditious and economic disposal of obviously uncontested matters is not defeated by frivolous denials or claim.”

[62] I cannot fault the conclusion reached by the learned judge in the Court a quo that whereas some disputes had been raised, there were neither genuine nor real nor material or relevant to the application. It could not be seriously disputed that parties had agreed on a verbal month to month lease in terms and conditions claimed by the Respondent.

[63] On the issue whether the matter has been settled between the parties, the learned judge in the Court a quo rightly stated that in order to correctly answer the question, there was a need to examine closely the letters exchanged between the parties between 11 May 2005 and 24 May 2015.

[64] The first letter from the Appellant to the Respondent was dated 11 May 2015 in which it was proposed that the matter be settled by the Appellant paying the Respondent a sum of E500,000.00 It was also proposed that the Appellant be allowed to harvest the sugar cane and be permitted to remove the cattle from the farm. Furthermore it was proposed that the proceedings between the parties under case No 454/2015 be withdrawn.

[65] The Respondent rejected this offer by letter dated 12 May 2015. Then by a letter dated 15 May 2015, the Respondent made a counter-offer that the Appellant vacate the farms by 16:30 hours on Sunday 24 May 2015, that it removes all its employees and movables from the said farms. The sugar cane and all the other crops were to be left on the farms and were not to be harvested by the Appellant. The offer was a final one and was not open to negotiations.

It was to be open for acceptance until 11:00 hours on the 18 May 2015. The arrea rentals claim was to be dropped together with the claim for costs.

[66] The Appellant did not adhere to the deadline put forward by the counter offer, allegedly due to having received it late on the same day of 18 May 2015. The Appellant accepted to vacate one of the farms Horse Shoe by 16:30 Hours on 24 May 2015, but commencing the process of vacating the E1 Ranch property immediately which would not to be completed by 24 May 2015 due to the problems explained by the Appellant.

[67] There were, therefore, several offers and counter offers from 18 May 2015 when the Appellant made a counter offer and on 20 May 2015 when the Respondent made another counter offer to the Appellant open for acceptance until 10:00 Hrs. on 21 May 2015. The final counter-offer was only responded to by the Appellant on 29 May 2015, proposing that the Respondent should formulate a settlement but by this time, the final counter-offer had lapsed. Therefore, it is clear that the dispute had not been settled.

[68] The next issue is whether the counter-claims ought to have been adjudicated upon together with the claim. The learned judge in the Court a quo held that the counter-claim could be raised through an independent action by the Appellant. In this connection the learned judge stated;

[41] Whilst it is true that the Respondent’s claim can never be extinguished by the Applicant’s claim, and whilst it is further true that such a claim can always be instituted anytime, the Applicant has per replying affidavit acknowledged its indebtedness to the Respondent to at least a sum of E1, 257,887.13. It has also acknowledged that such a sum can be set off against what is owed, otherwise the balance of the Respondent’s claim can always be raised through an independent action which it is at liberty to institute”

[69] The learned judge acknowledged that the Appellant had alleged that its counter- claim was worth more than what it owed to the Respondent, but observed that the position of the law is that the success or otherwise of a counter-claim is not confined to it being raised as such. Reference was made to Herbstein and Van Winsen’s “The civil Practice of the Supreme Court of South Africa,” 5th edition at page 667 where it is stated as follows;

“ A counter-claim is a claim which the defendant could have instituted by way of a separate action against the Plaintiff and it has been stated that the fact that it has been brought as a counter-claim should not deprive the defendant of any rights which he would have had with regard to claim in convention”

[70] Another reason the learned judge gave for not dealing with the counter-claims was that the Appellant would not be prejudiced by the matter being proceeded with without the counter-claim which could always be instituted as an independent claim. The third reason the learned judge gave was that the Appellant’s counter claims were not liquid, which made them not to be easily resolved in the sense that they would require a fully fledged trial to resolve them. Indeed the Appellant admitted that it had included scantly details of the counter-claims.

[71] In my view, the learned judge gave sound reasons for not dealing with the counter claims which needed to be resolved through a trial. It was therefore not necessary to refer the claim for trial merely because the counter-claims could not be decided on the papers.

[72] For the foregoing reasons, I find no merit in this appeal. Accordingly I make the following order:

1. The appeal is dismissed

2. The Respondent is awarded costs including certified costs of

Counsel.

FOR THE APPELLANTS: Adv. P. Flyn

FOR THE RESPONDENT: Adv. G.I Hoffman sc

36